The Economic Impact of Violence in LAC: Implications for the EU

11 Jul 2017

By José Luengo-Cabrera for European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageEuropean Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS)call_made on 24 May 2017.

Violence and the fear of violence create, inter alia, significant economic disruptions. While violent incidents incur costs in the form of property damage, physical injury or psychological trauma, fear of violence alters economic behaviour, primarily by perturbing consumer patterns but also in diverting public and private resources away from productive activities and towards protective measures. Combined, they generate significant welfare losses in the form of productivity shortfalls, foregone earnings and distorted expenditure – all of which affect the price of goods and services. Measuring the scale and cost of violence has, therefore, important implications for assessing the effects it has on economic activity.

It is, however, difficult to estimate the wide-ranging economic externalities generated by violence. Consequently, the scope for quantifying them is restricted to what is tangibly measurable and for which reliable data exists, namely the monetary costs engendered by violent incidents and the financial expenditure allocated to contain or prevent them. Although it provides an incomplete diagnostic of the multidimensional economic impact of violence, calculating the costs associated with it is important for gauging the magnitude of the problem. In this vein, the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP) has developed a global model using an accounting method that aggregates 16 indicators related to containing, preventing and dealing with the consequences of violence. The model integrates both direct and indirect costs of violence as well as a ‘multiplier effect’. Direct costs include medical expenses for victims of violent crime or expenditure associated with the security and justice systems. Indirect costs include lost earnings due to productivity losses that arise as a consequence of crime or fear of crime. The ‘multiplier effect’ represents the opportunity cost of violence: in other words, the investments in productive economic activities that could have been accrued if the expenditure on violence had not been necessary.

In Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), where the rates of violent crime are disproportionately higher than in other regions, the costs arising from violence continue to outweigh the expenditure devoted to prevent or contain it. By calculating and disaggregating the cost of violence, the IEP model can serve as a benchmark for assessing the cost-effectiveness of public security programmes and inform decisions on adjusting the levels of violence-containment expenditure. For the EU in particular, it can be used as an early warning tool via its capacity to track trends in the levels (and concomitant costliness) of violence. This is particularly relevant following the calls made in the 2016 EU Global Strategy (EUGS) for a ‘more responsive Union’ at a time when intensifying political acrimony and violence in Venezuela have exacerbated its economic woes, bringing the country to the brink of a humanitarian crisis.

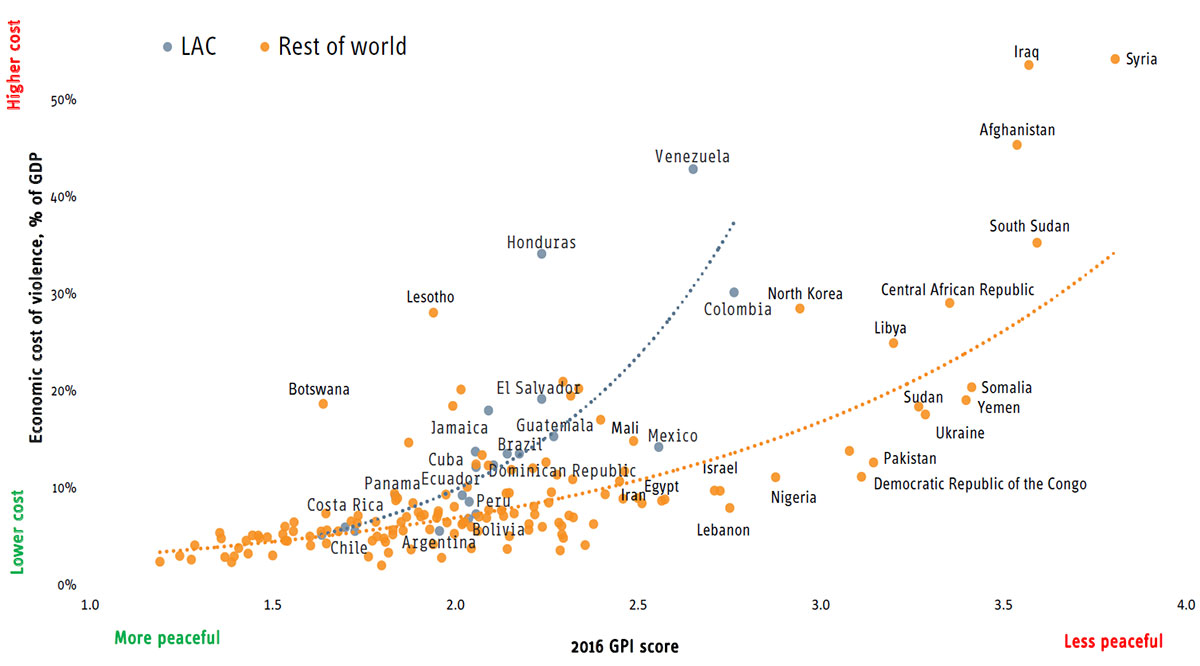

GPI score vs cost of violence (% GDP), 2016

Violence in LAC

The LAC region can be considered to be the most violent in the world, particularly when measured by homicide levels. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the average homicide rate for the region was 24 per 100,000 people in 2015. This is close to four times the global average and more than twice the rate of 10 per 100,000 people that the World Health Organisation (WHO) considers as epidemic. As a region that hosts less than 8% of the global population, it generates 33% of global homicides. Brazil, Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico and Venezuela alone accounted for one in four intentional murders worldwide in 2016, shedding light on why 23 out of the 25 most homicidal cities in the world are in LAC.

In addition, many countries of the region are disproportionately affected by other forms of violent crimes like robbery, assault or rape. Based on data from the Latinobarómetro, an annual public opinion study across 18 LAC countries, an average of 36% of surveyed citizens reported being victim of a non-lethal violent crime in 2015 – up from 29% in 1995 - with levels as high as 48% and 46% in Venezuela and Mexico. In turn, survey data from Gallup shows that the regional average for those reporting to fear crime was 52% in 2015, with numbers as high as 76%, 63% and 62% in Venezuela, Brazil and El Salvador, respectively.

A correlation analysis from IEP’s 2016 Economic Value of Peace report shows that LAC countries where citizens reported the highest levels of victimisation were also those with the lowest levels of peacefulness, as measured by IEP’s Global Peace Index score (GPI). These were the same countries for which the cost of violence were among the highest in the region and where the correlation with their GPI scores was found to be non-linear, i.e. as the level of peace decreases, the costs associated with violence increase exponentially – a pattern that is consistent outside LAC.

Counting costs

In a region where organised crime syndicates violently compete for lucrative drug trafficking routes and territorial control, the political economy of the drug trade is known for fuelling violence. According to the UNODC, 30% of homicides in LAC are attributed to drugrelated activities. Compounded by the widespread availability of firearms, high levels of income inequality and the inept capacitation of law enforcement entities to address impunity, violence remains a pervasive phenomenon in LAC.

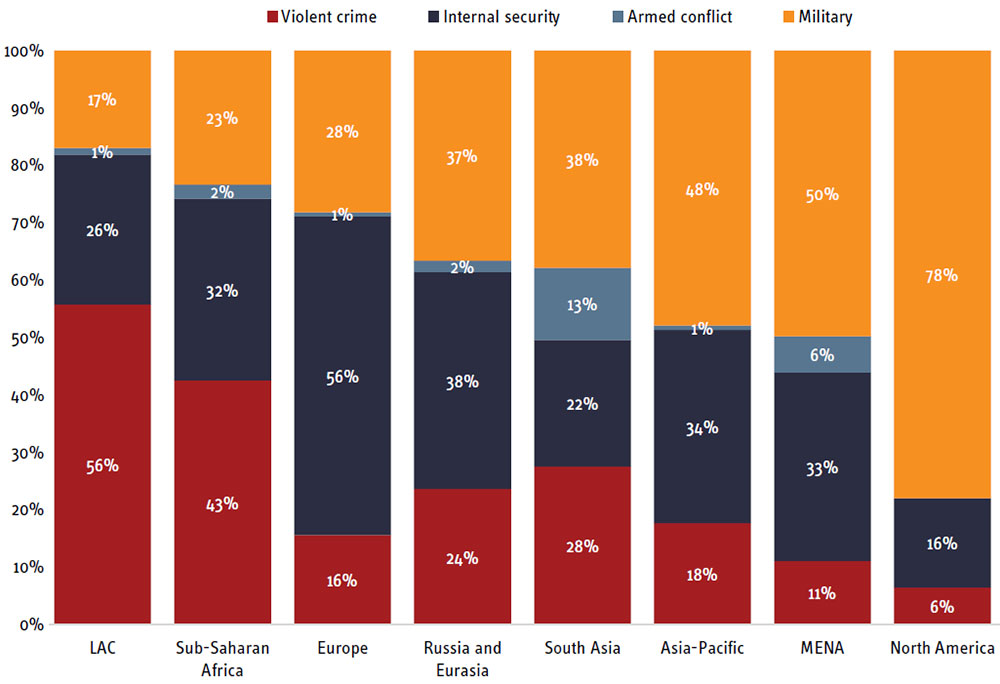

Regional per capita cost of violence by expenditure type, 2015

With only 20% of homicide cases resulting in convictions across the region, criminals continue to face low opportunity costs from engaging in violence. In fact, the high degree of impunity is one of the main reasons why the incentives for criminality remain attractive. This is reflected by the large economic returns that are being generated from engaging in the narco-trafficking, kidnapping and extortion activities of organised crime, a phenomenon that IEP explores in its 2017 Mexico Peace Index.

Given the multiplicity of economic and institutional factors affecting violence, much of the research has been focused on understanding the drivers of violence. Consequently, systematic evaluations of its economic impact remain relatively limited. This is principally due to the fact that there is no universally agreed method for aggregating the current and future financial effects of violence. Notwithstanding, the IEP model finds its added value through its capacity to calculate the magnitude of violent-related costs and expenditure, with values expressed in constant purchasing power parity (PPP) terms – a method that permits cost comparability between countries.

LAC in global comparison

IEP estimates show that the global economic cost of violence was $13.6 trillion (PPP) in 2015. LAC countries accounted for 10% of this total cost. Expressed as a percentage of GDP, the average regional cost was 13.9%, higher than the global average of 10.2%. In per capita terms, violence cost the average LAC citizen $1,518 in 2015.

Homicide alone accounted for 47% of the total cost of violence in the region, more than the combined costs from expenditure on internal security (16%) and the military (14%). When broken down by categories of per capita expenditure, LAC had the highest proportion of costs related to violent crime (56%) across all regions. This can be evidenced by the exceedingly high rates of violent crime in the Northern Triangle countries, as highlighted by El Salvador, where the rates of homicide and assault in 2015 reached a whopping 103.3 and 61.2 per 100,000 people, respectively.

Moreover, the cost of violence in LAC has witnessed the largest surge worldwide over the past decade. This has been driven by rising rates of violent crime in Central American and Caribbean countries, notably Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador and Jamaica, which are in the top ten ranking of countries with the highest homicide rates in the world. Since 2007, the cost of violence in this sub-region saw the largest increase (73%). This surge was higher than the MENA region (43%), which had the two countries with the highest cost of violence as a share of GDP in 2015: Syria and Iraq. From 2007 to 2010, the South American sub-region witnessed the highest rate of increase (38%) in the cost of violence, but this rate has since flattened, with a notable decrease of 6% between 2014 and 2015. This was probably driven by the steady drop in violent crime rates in Colombia, especially homicide rates, which in 2015 reached their lowest levels since 1974.

Implications for the EU

Following the calls made in the EUGS for a ‘closer Atlantic’, the EU has reasserted its willingness to expand and deepen cooperation with LAC countries, particularly by engaging in peacebuilding and fostering human security through a more ‘integrated approach’. With regards to crisis prevention, it highlighted the need to translate early warning into early action. In this endeavour, the EUGS called for more frequent reporting and proposals to the Council, but also greater engagement in preventive diplomacy and mediation by mobilising EU Delegations and Special Representatives, as well as deepening partnerships with civil society.

Given the high costs of violence in LAC, systematic assessments of the economic cost of violence can enhance the scope for EU preventive action. This is particularly relevant within the context of the worsening political and economic crisis in Venezuela. At a time when food and medical shortages have become a daily occurrence and intensifying political acrimony has prompted renewed anti-government violent protests, the country’s GDP has contracted by 18.7% while its annualised inflation has skyrocketed to 800%. The IEP model estimated that violence cost the Venezuelan economy $79 billion in 2015 – equivalent to 42.8% of its GDP – placing it fourth in the global economic cost ranking after Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan.

The wide-ranging effects of this crisis are already affecting consumer patterns, particularly due to increased fear of victimisation but also as a result of foreign currency shortages that are making it hard for Venezuelan businesses to purchase imported capital goods. In addition, insecurity is skewing expenditure away from much needed social programmes and into the police and the military while infant and maternity mortality rates have gone up by 30% and 60% since last year, with the number of malaria cases incrementing by 76%. This sheds some light on the negative externalities that violence can have on the provision of public health and economic productivity more generally.

As part of the efforts to develop a political culture that is more responsive to crises akin to the Venezuelan one, the IEP model serves to complement the EU’s early warning toolbox, notably in helping policymakers identify deteriorating trends. Moreover, it can also be used to benchmark security and development aid expenditure, particularly when there are large discrepancies between the sums invested for the prevention or containment of violence and the costs generated by it.

To put things in perspective, the EU’s financial allocation of the multiannual indicative programme for LAC totalled $1 billion (€925 million) for the 2014-2020 period – representing just 0.1% of what violence cost the region in 2015. Ahead of the upcoming 2017 EU-CELAC summit in October, this should serve as a stark reminder of the need to adjust violence-containment expenditure in the most violent LAC countries.

About the Author

José Luengo-Cabrera is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Economics and Peace.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.